My first home built Puzzle

After the successes with creating both Square Sticks and Cubes, I had to go do something with them; and see if I could create a puzzle. I decided to make some of Stewart Coffin’s designs, and having been in touch with him, he very graciously gave me permission to try to recreate any of his designs, and encouraged me to do so. With that endorsement, I was off and running. Well, almost!

I had to work out which puzzle I was going to create. There’s so many to choose from that it’s not an easy decision. In the end, I decided to create something that I didn’t already own, so I’d be adding to my collection if it turned out to be any good. So I settled on a copy of STC #214, the Involute puzzle. The Involute is the third in a series of puzzles from Stewart Coffin, each an improvement over the predecessor.

The first was Convolution, a 4×4 interlocking cube which requires a rotation in the solution. Due to the rotation, some material needs to be removed from one of the cubes in the solution (if you have a tight fit) to allow the rotation to happen. You can read my review here. Stewart Coffin notes that given the rotation, and the nature of cubes (which don’t like to be rotated when hard against one another), that this design could be improved. In his book “The Puzzling World of Polyhedral Dissections”, he leaves it to the reader to see if they can find a solution to this problem.

At the same time, Stewart Coffin had already solved the problem, and created STC #198, Involution. Again a 4×4 cube with a rotation required in the solution, but this time because of the design of the dissection, no material needs to be removed from the pieces to allow the rotation. I’ll not give away how this is done, as it would spoil the puzzle, but I will say it’s a simple and clever solution! I was able to play with one of Scott Peterson’s copies that he had made on my recent visit to see Scott, so I can say I’ve solved both the Convolution and Involution puzzles at this point.

The third in the series is STC #214, Involute. This is the final puzzle in the series, and is again an improvement over the Involution and Convolution. Again there is a rotation required in the puzzle, and again, no material needs to be removed for the rotation to take place. There’s an extra trick in this puzzle, that I’ll get to in a bit which makes it just that bit more devious.

All three puzzles in the series look identical from the outside, each having the same cross pattern on all six faces, so without knowing which puzzle you have in your hand, it could easily be any one of the three. Have I mentioned that this Coffin is a devious bloke?

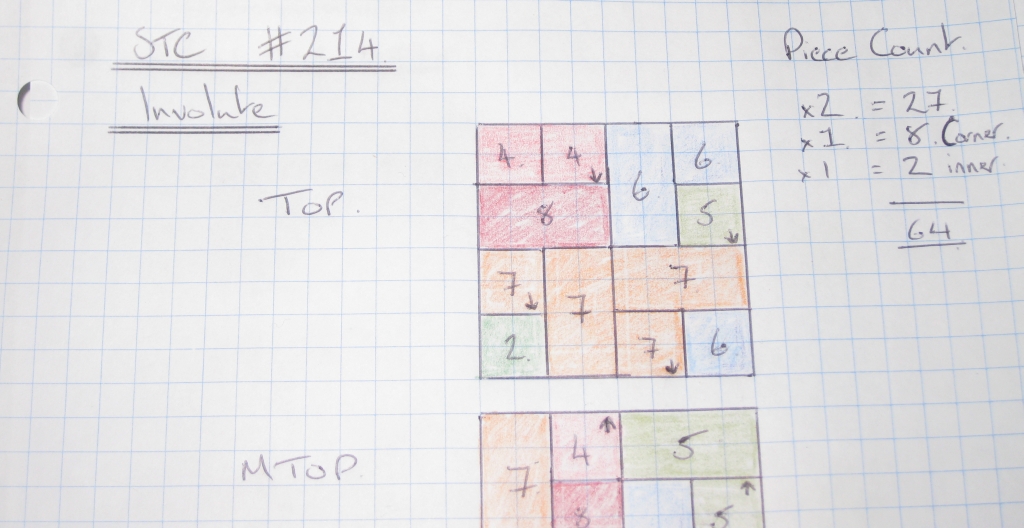

Thanks to Allard and Kevin who both reviewed their copies of the Involute puzzle, I was able to model the pieces in burr tools, and from that create myself a parts list and a gluing diagram to be able to build the puzzle.

Given that it took several hours to create the diagrams, including the time to create the model in burr tools and so on, I’m not going to give you the whole thing. Not to mention it would spoil how to solve the puzzle (or would it – I’ll come back to that thought). But the image above gives you an idea of what I created.

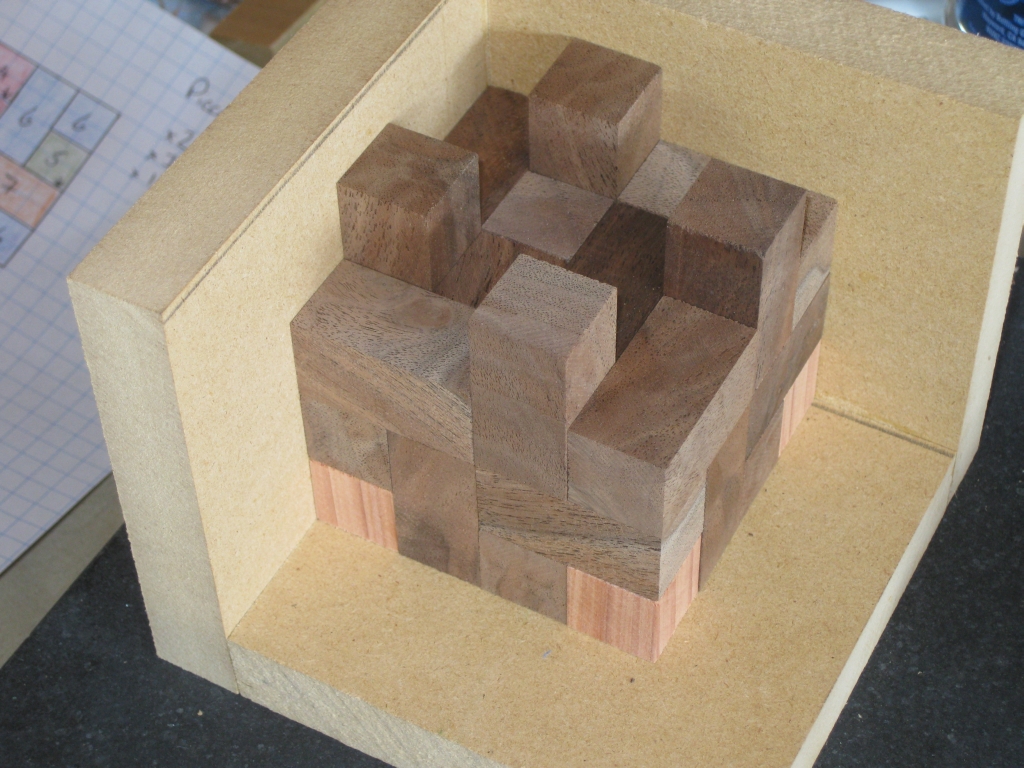

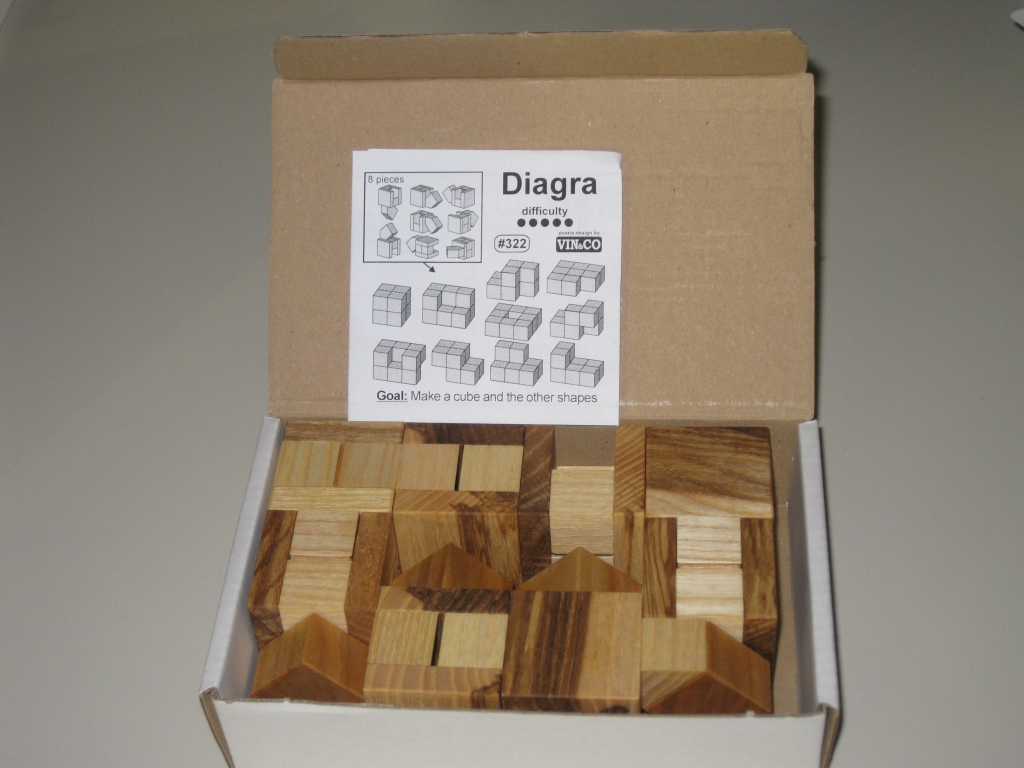

With the design in hand, I went off to the saw, and using the crosscut sled and my stops, I cut all the necessary cubes to make the puzzle. There’s quite an array of pieces there when you see them all sitting together. Also in the picture is one jig I hadn’t talked about previously. This is my cube gluing jig. It’s not overly complicated, just three pieces of MDF cut and glued together to hold a 4×4 cube cut to my 3/4″ stick size which has all edges at 90 degrees, and has been waxed to prevent any glue from sticking to it. I also have three ‘end panels’ which will distribute the clamping pressure evenly across all the blocks so as not to twist the blocks while the glue dries.

At this point I made something of a realisation. Sitting looking at this array of blocks, and my gluing diagram, gluing up one of these puzzles is hugely complicated. You’re working in three dimensions gluing any number of pieces together, all of which needs to be accurate, and with no glue squeeze-out. If you thought Ikea furniture plans were Convoluted, then this is much more challenging!

Next up I placed all the pieces into the gluing jig, to match my plans. This serves a couple of purposes. Initially, it shows me how good the fit is, and also verified that my plans were correct (at least in as much that I had the correct number of pieces). The other benefit to the dry fit is that it allows me to select which pieces I want to put where in the puzzle. Looking at the grain in the wood, I can select the ‘nicest’ grain to be on the outside of the puzzle, or look at creating grain patterns by selecting pieces carefully from the pile. Given that this was a first ever attempt, I wasn’t too concerned with the grain pattern, but I didn’t entirely ignore it either.

Since this was the first glueup I’d be doing, I decided to go with gluing up two layers at a time. This meant that I didn’t have to work quite as quickly to get the clamps on the jig to ensure that tight fit I was going for. Fortunately, the way the pieces go together, there is a flat surface after every second layer, which was ideal as a stopping point. I also have a smaller glue bottle, where I’ve decanted some of the glue from my big bottle. This small bottle has a fine nose, and is much easier to work with that the full sized bottle. Given the small amount of glue I’d need for each piece, this is the only way to work.

With all the pieces separated into layers, I was as ready as I was ever going to be to start putting this together into a puzzle. Fingers crossed!

Working reasonably quickly, I glued up the first two layers, and thanks to tips from Scott Peterson, I managed to do so with little to no glue squeeze-out. That’s pretty important since any glue squeeze-out will glue blocks together that shouldn’t be, making the puzzle unsolvable. You’ll notice the fairly large block of wood on the top of the gluing jig in the photo on the right. That’s because I only have two layers build at this point, so the puzzle is half way inside the side plates. I needed to add some height to be able to clamp the puzzle effectively.

After the glue had set, I came back and added the remaining two layers, building on the two I already had. This time, you can see that the puzzle fills all the space, and there are no extra spacers required. I then had to wait a few hours for the glue to dry properly before I could take the clamps off, and see whether I had created a puzzle or a paperweight.

They may have a been a few of the longest hours I have experienced in a long time. My fiancée was about ready to kill me, as I wanted to go take the clamps off and see what I had, she kept telling me to leave it alone. I was like a kid on Christmas morning waiting to see what presents I had. I could barely sit still! When things had been left for long enough, I was finally allowed to go take the clamps off and see what I had.

I should note at this point, that I have never solved an Involute puzzle prior to making this one. Given that rotations are required in the solution, Burr Tools can show that there is a solution, but it can’t animate the assembly for you (or in my case the dissassembly), so I have no idea how to take the puzzle apart. I’m now in new territory, and given that I don’t know how to take things apart, or whether the pieces are glued together correctly, and not glued to one another I know this is going to be interesting!

Since I know where the key piece is, I can remove that fairly easily, but then spend the next ten minutes pushing and pulling on various pieces hoping that something else will move in the puzzle. I can see that there is movement in the pieces, so at least it’s not all glued together, but I am having real problems in finding the second move. The pictures that follow were taken by my fiancée, so are unedited as I make progress. That grin on my face is real!

As I mentioned, I’ve never solved the Involute before, so I had no idea how the puzzle was supposed to come apart. The key piece in the puzzle is really well hidden, and without knowing where it was I would have struggled to start, especially not knowing if the puzzle was entirely glued together at this stage. The second move is also very clever. One thing that Stewart Coffin regularly has in his designs is pieces which are created so that the average person will hold the puzzle in such a way that you will be holding the piece you need to move, effectively pushing the puzzle closed and preventing it from being opened. The Involute is no different, and has this very same trick to allow move two. The look on my face when what looked like half of the puzzle slid to the side perfectly must have been quite the picture. I think for me not only was I solving a puzzle for the first time, which always brings a smile to my face, but also it was a puzzle I had built, and seeing it work the way it is supposed to is an ever bigger achievement.

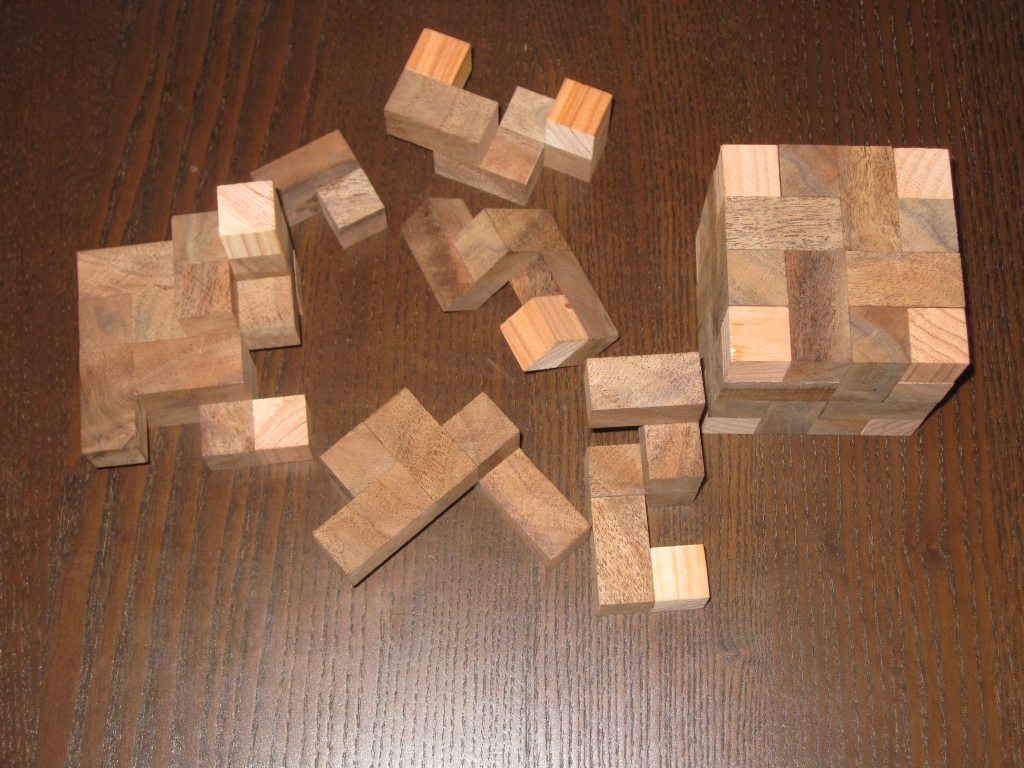

I took the puzzle fully apart, and was left with the eight individual pieces sitting on my sofa, with a huge grin on my face. I then realised that I had absolutely no idea how to put the whole thing back together! In my excitement of taking the puzzle apart, I wasn’t paying any attention to how the pieces were coming apart! I then spent the next 15 minutes with my gluing diagram trying to put the puzzle back together. Remember I mentioned that having the full diagram may not help that much! I did get there, and the smile on my face seeing the puzzle back together was truly from ear to ear.

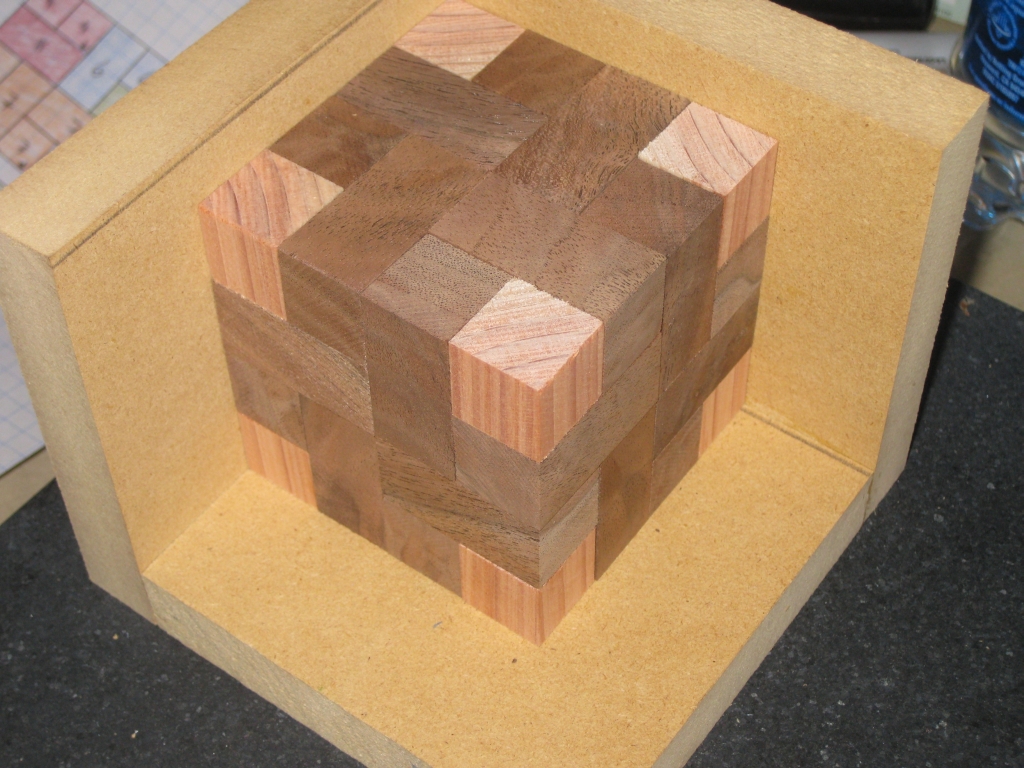

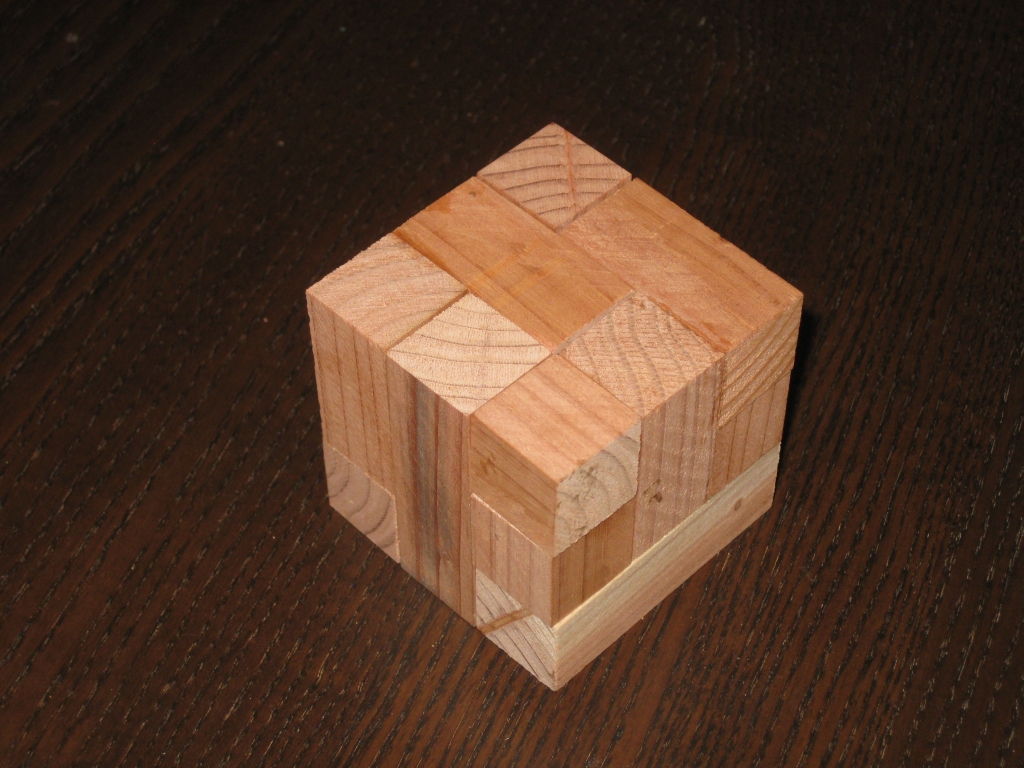

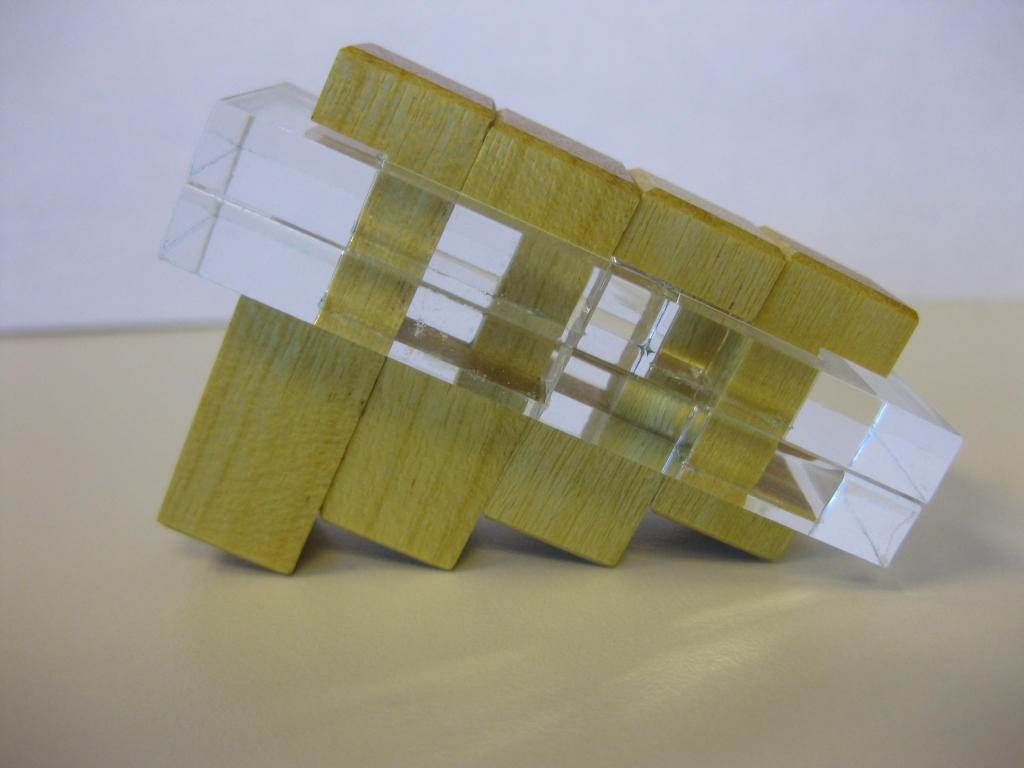

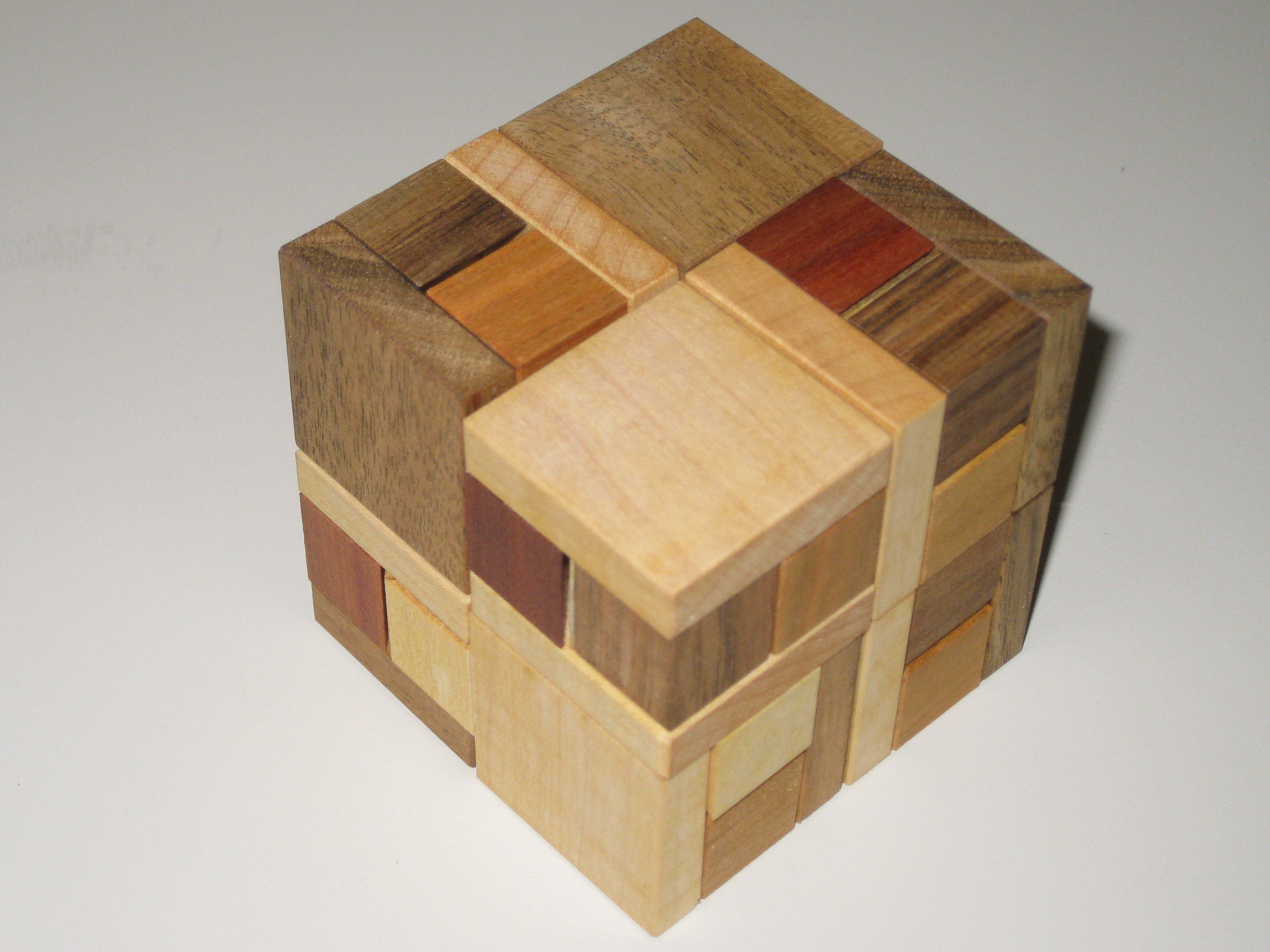

The rotation in the puzzle works perfectly, and I haven’t removed any material from the rotational piece to make that move easier. The fit of the pieces is superb. It’s difficult to tell individual pieces apart as you can see from the closeup above. This makes finding how the pieces come apart even more difficult that if the pieces fitted loosely together as there is no movement between the pieces. In case you’re wondering, that tiny gap that looks like there’s a chunk taken out of one of the pieces isn’t tear-out as a result of a poor cut, but was some natural holes in the walnut. It’s also worth noting here that there is no sanding done on any of the pieces, these are all straight off the saw. Many people in the puzzle community have noted that sanding reduces the accuracy of the pieces, and that a good clean cut can have every bit as good a finish as a sanded piece, perhaps better, since sanding is effectively scratching the surface.

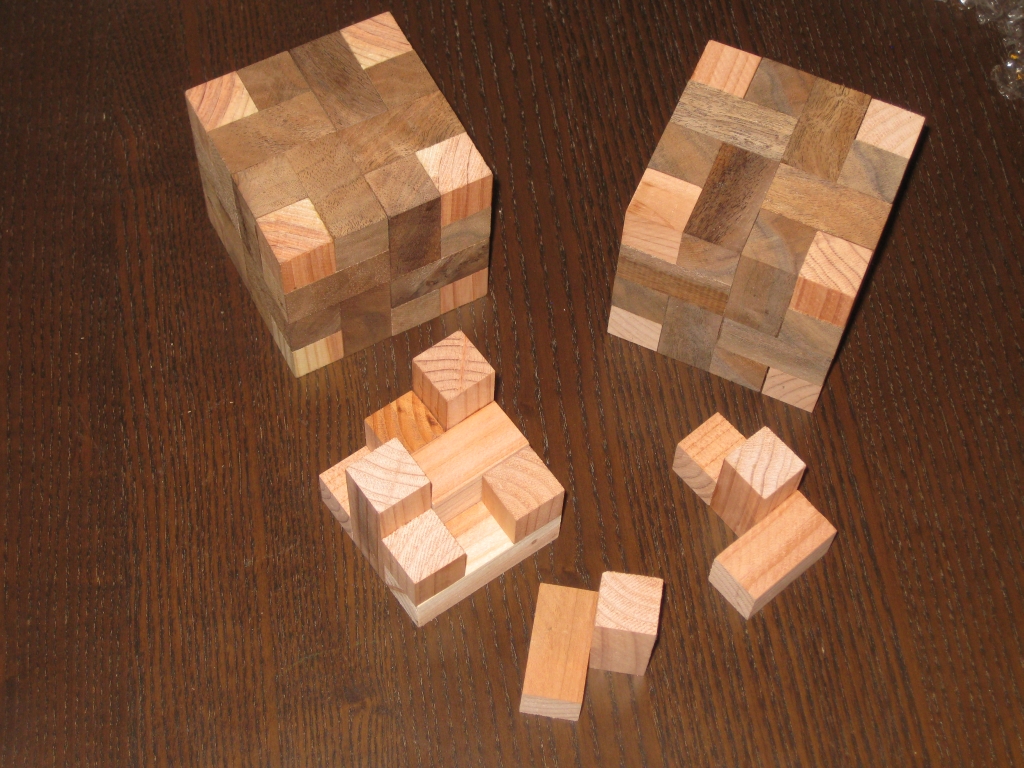

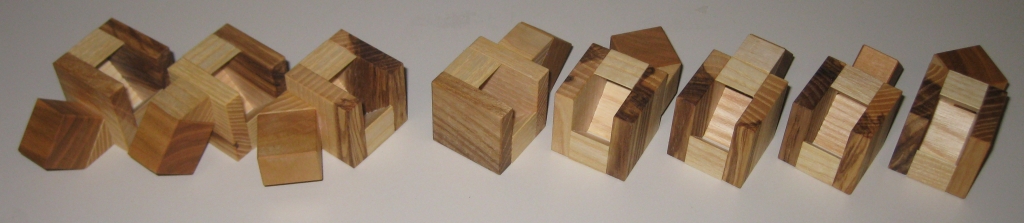

To prove that it wasn’t just a fluke and this was a one-off, I went off and created a second copy of the Involute. So what you’re seeing here isn’t some clever photography, but the two copies side by side.

And just to show that it works, there’s a partially assembled version next to the fully solved cube.

I was really happy with the results. Over the weekend I produced two copies of the involute puzzle, and both have a very snug fit, and I’d be happy to add these to my collection. In case you’re wondering, they’re made from walnut with redwood corners. And not to sound like an American advert trying to get you to place an order for something you didn’t want …

But that’s not all!

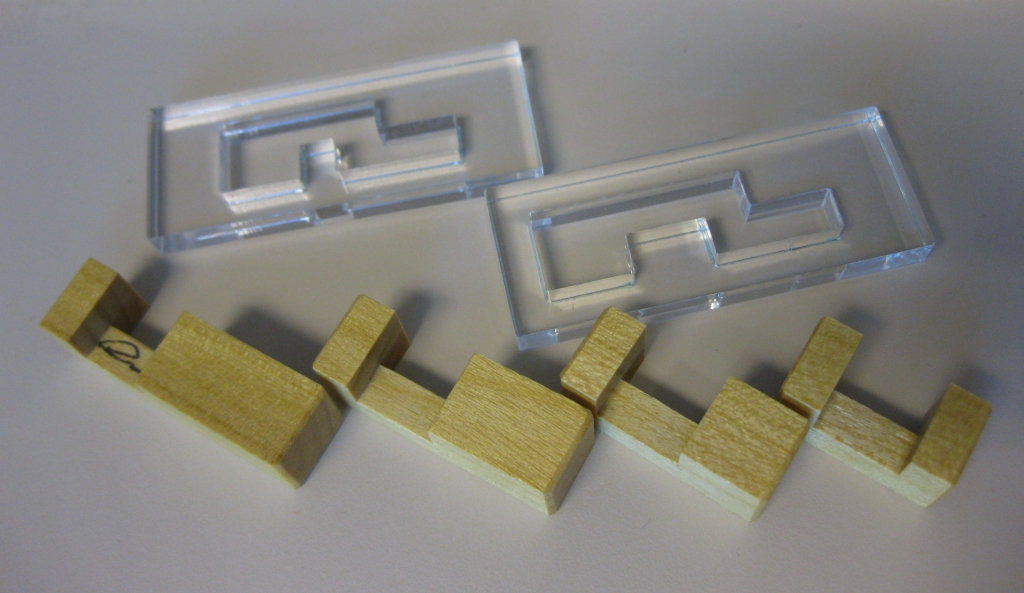

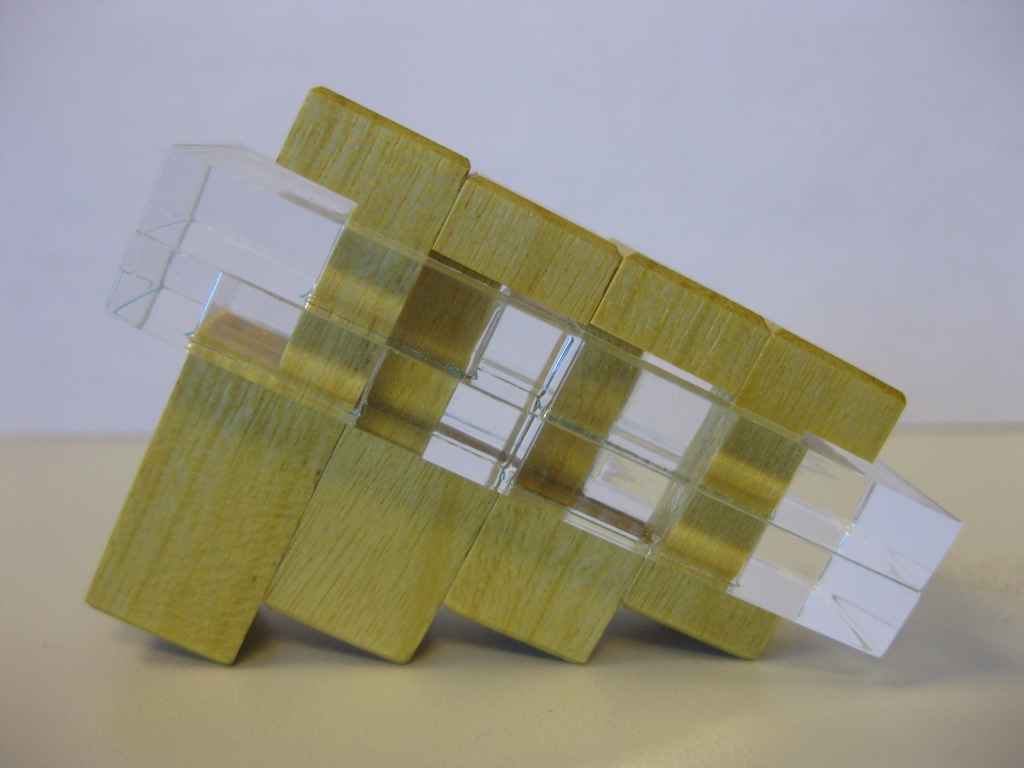

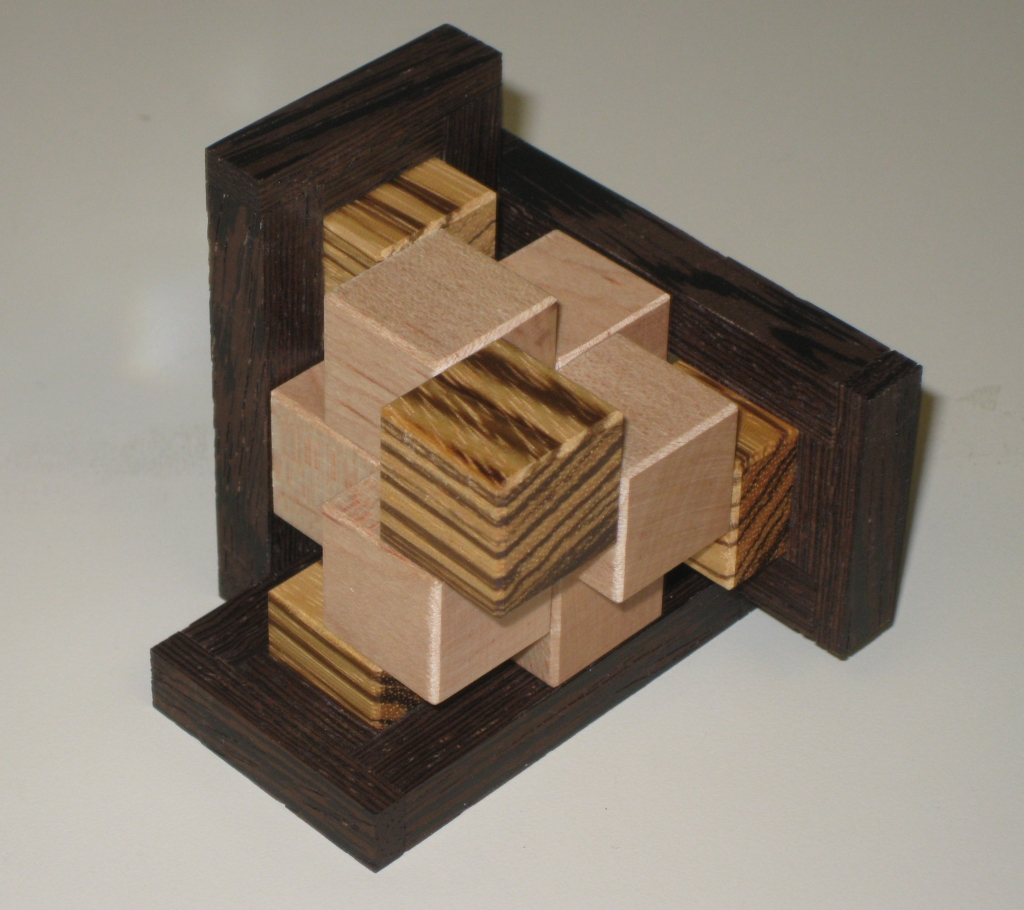

There’s another of Stewart Coffin’s designs that I’ve wanted to play with for a while. That’s his “Half Hour Puzzle”, STC #29. So I drew up the diagram for that, and made one of those too! The brilliant thing about the half hour puzzle is that even though Stewart coffin designed it to only have the cube solution, there are hundreds of possible solution shapes that can be made with the pieces. I’ve created a burr tools file with many of the solution shapes, so if you’re interested in a copy of the file, just let me know.

So there you have it. Three puzzles in one weekend, all which I am very proud of, and is the start of hopefully great things. As Allard has put it, “One day there’ll be a couple of us around who can say that we had one of the very puzzles created by someone the whole puzzling community now knows as the Juggler-guy! :-)” Maybe … one day.