During the Design competition at this year’s IPP I was able to play around with some of Jane and John Kostick’s new designs. In total there were three new designs from Jane this year, and despite not winning any awards, they are all great to play with, and much like the Tetraxis I wrote about yesterday, have a quality that makes you want to take them apart and put them back together. A lot.

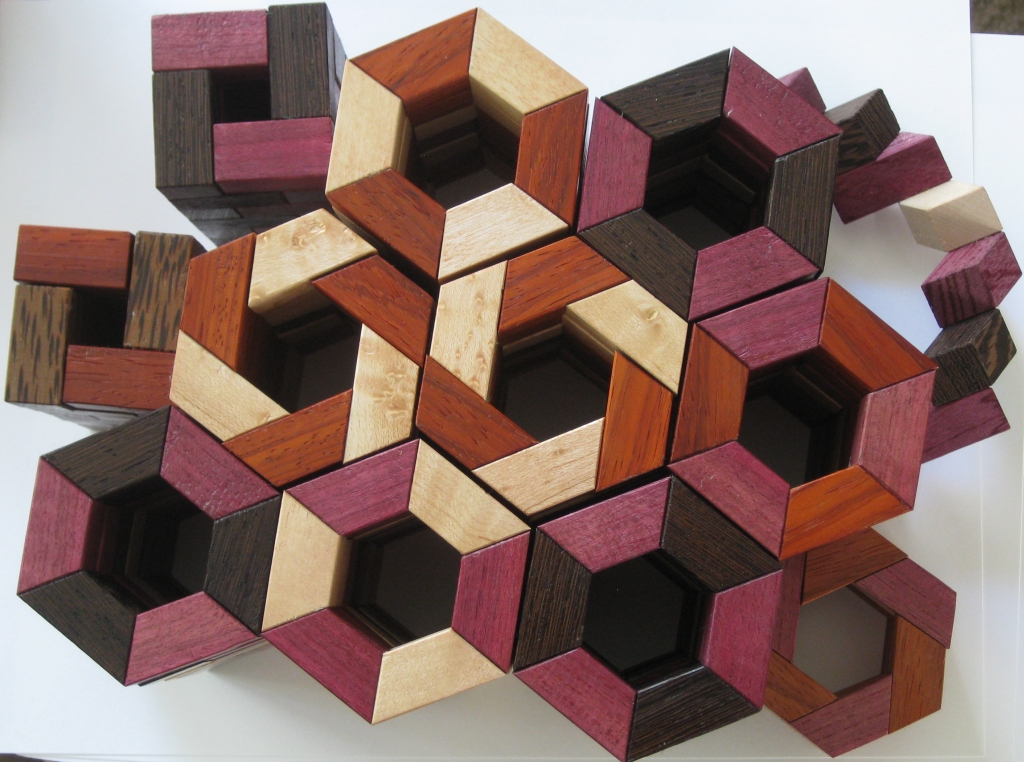

This year there were many more puzzling elements to the offerings so rather than just making the complete structure, you could spend a lot of time trying to make the other structures mentioned. First up is the 3 Layer Tetraxis array.

3 layer Tetraxis array

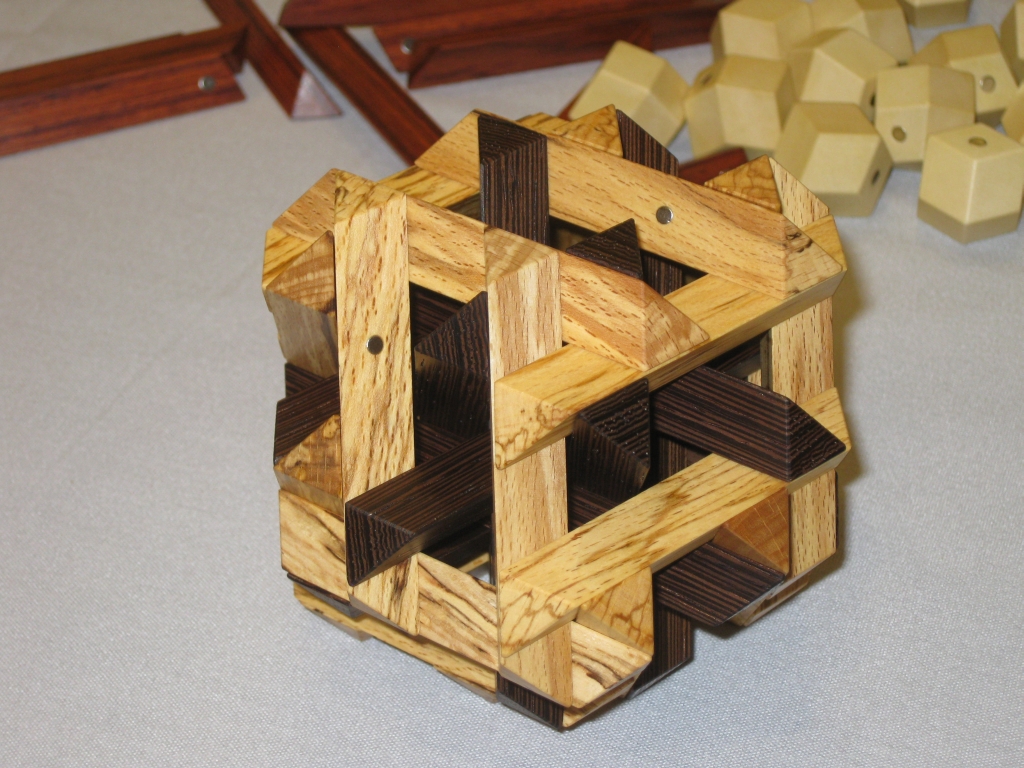

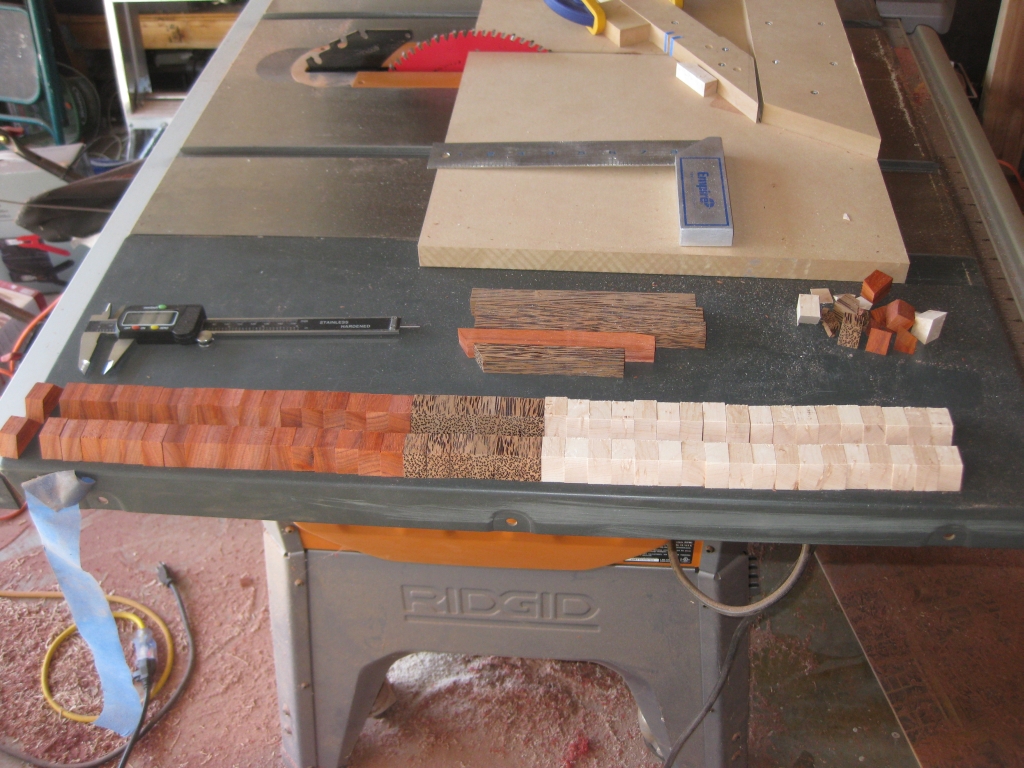

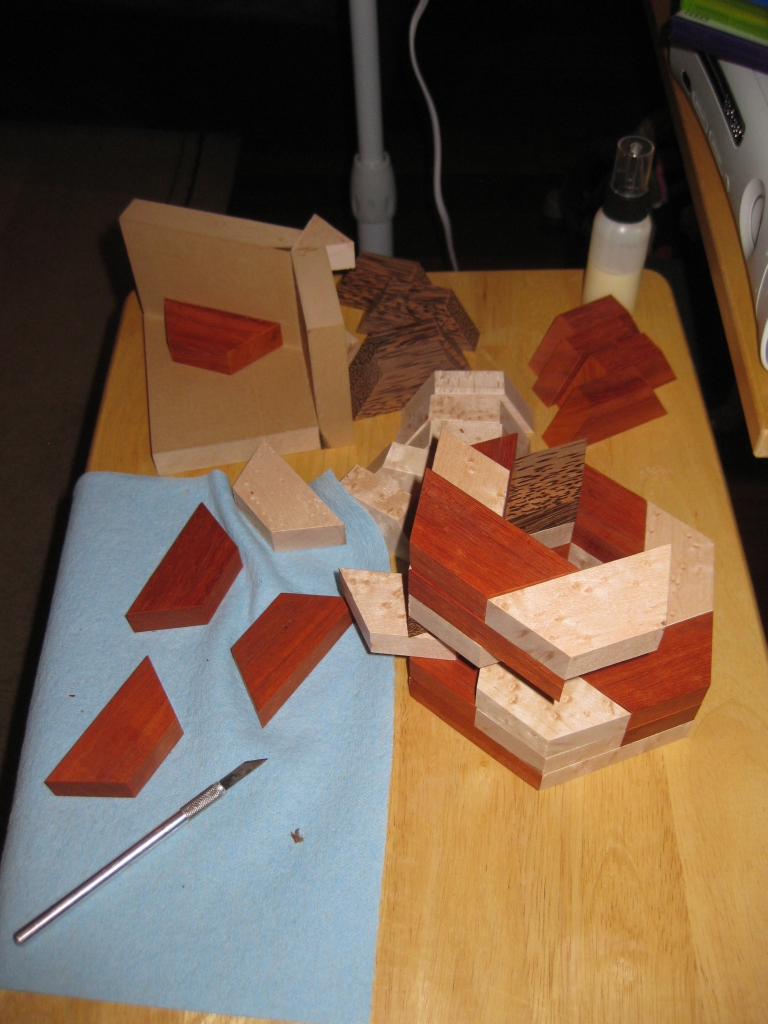

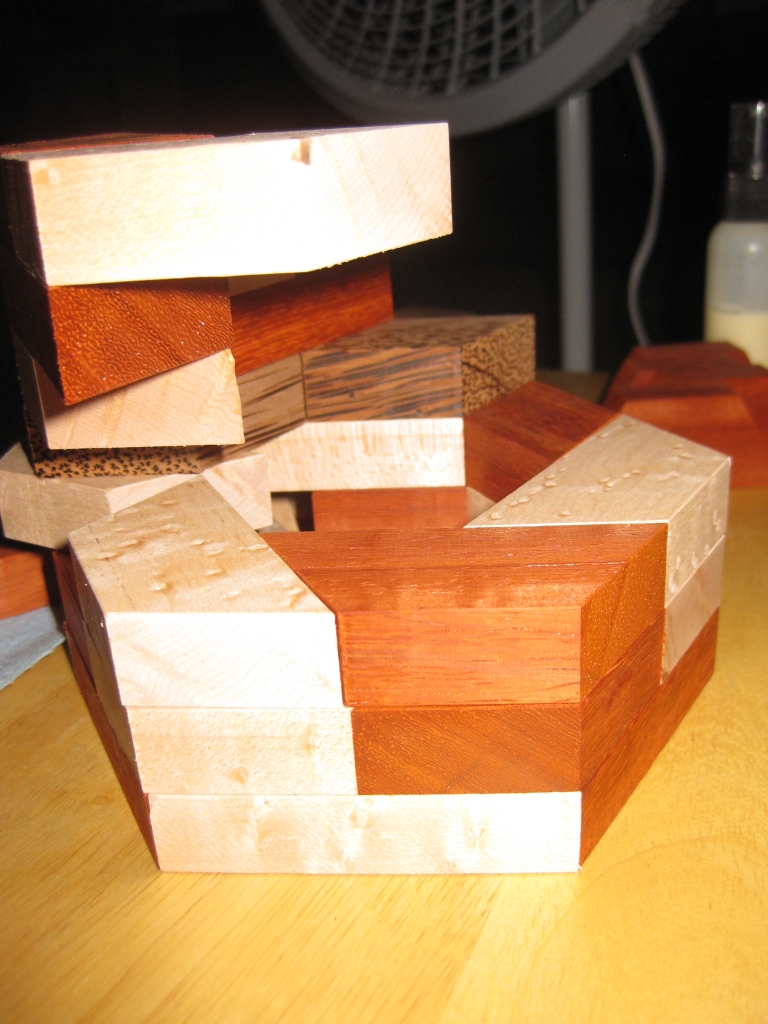

This is the largest of the three structures, measuring 4.5″ when fully assembled. (Thanks Allard for the correct size) Made from a number of exotic woods including Wenge, Maple, and at a guess Bubinga and Spalted Apple, the puzzle looks stunning. Jane’s top quality finish on the pieces is clear and the fit is excellent. As with the Tetraxis array I wrote about yesterday the pieces are embedded with magnets which hold the structure together, and help lead you to the solution.

I had a lot of fun playing with this puzzle. It has the initial appearance that it’s much harder than it looks which may have put some people off, but it’s so much fun to play with that you’re really missing out if you don’t.

There were seven challenges with the 61 sticks and blocks. None were overly difficult, however each creates a stunning structure which would look great in any display. Also it’s worth noting that all of the first three solutions can be made at the same time.

The challenges were to use the set of 61 sticks and blocks to put together seven compositions that symmetrically surround a center:

1. Using one block and the 12 longest sticks

2. Using the 12 blocks and the 12 mid-length sticks

3. Using the 24 shortest sticks

4. Combine 1 & 2

5. Combine 1 & 3

6. Combine 2 & 3

7. Combine 1, 2 & 3

Below are a few images showing some possible combinations, but I’m not going to show all the solutions, you can work them out for yourself!

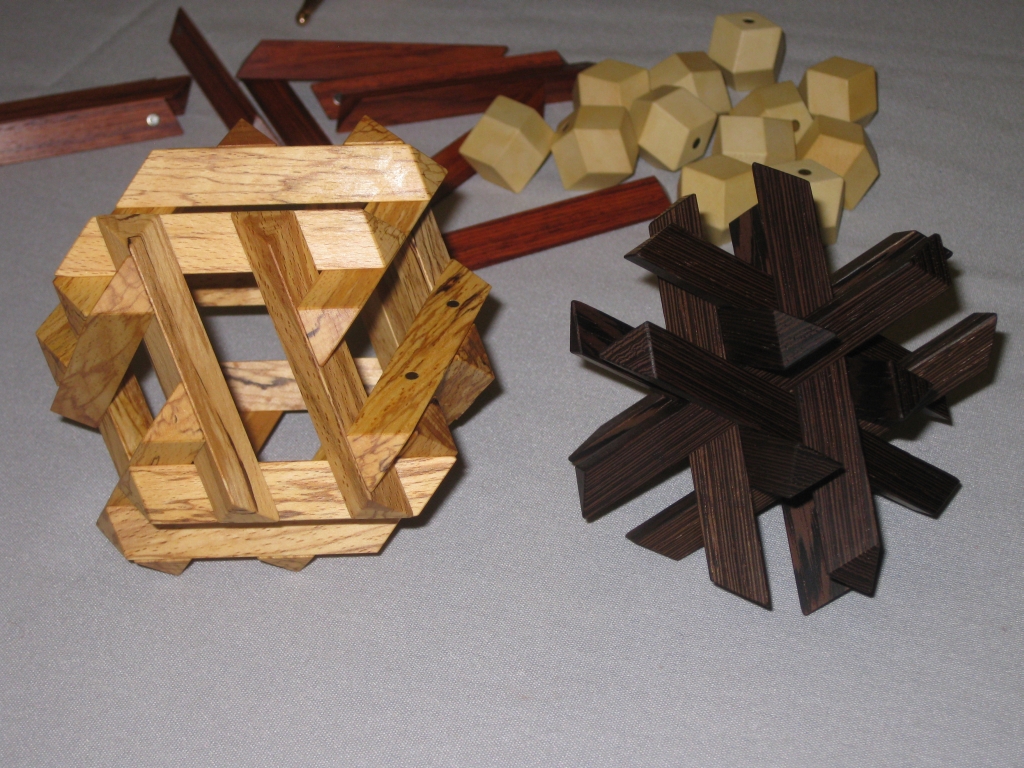

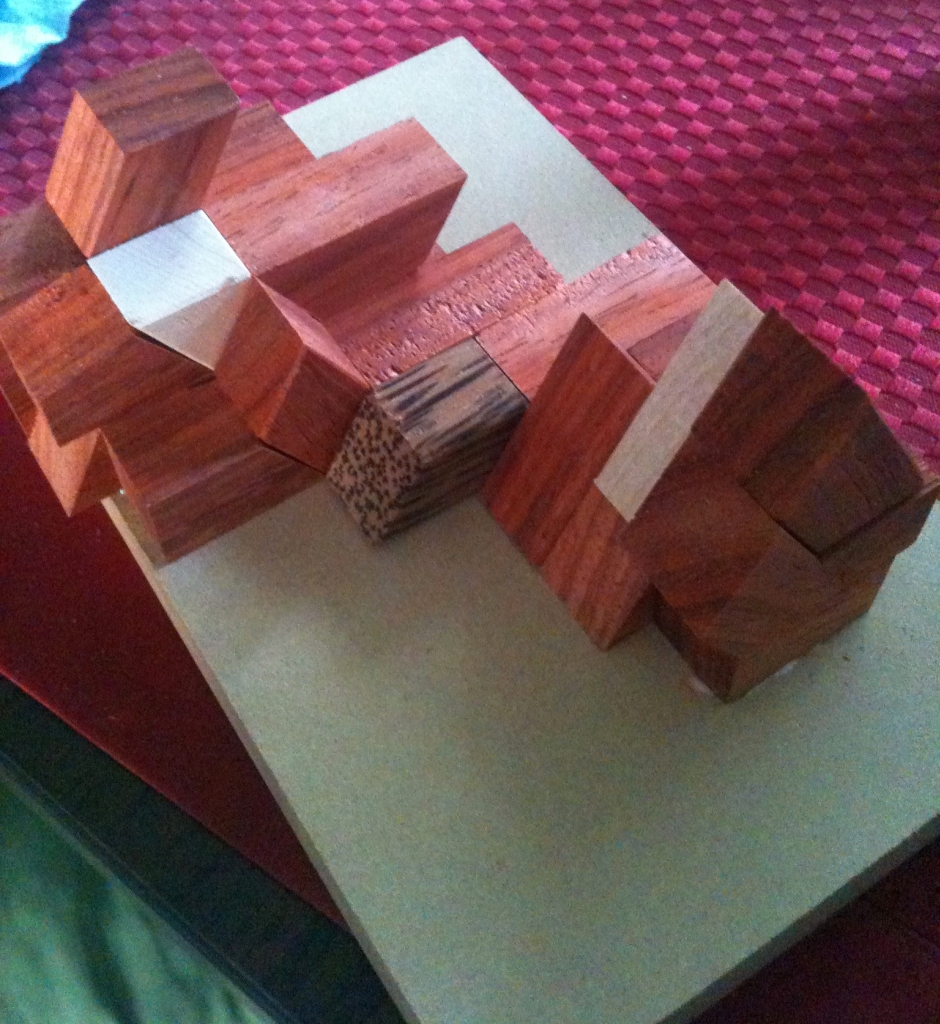

The outer ‘layer’ removed showing the inner structure.

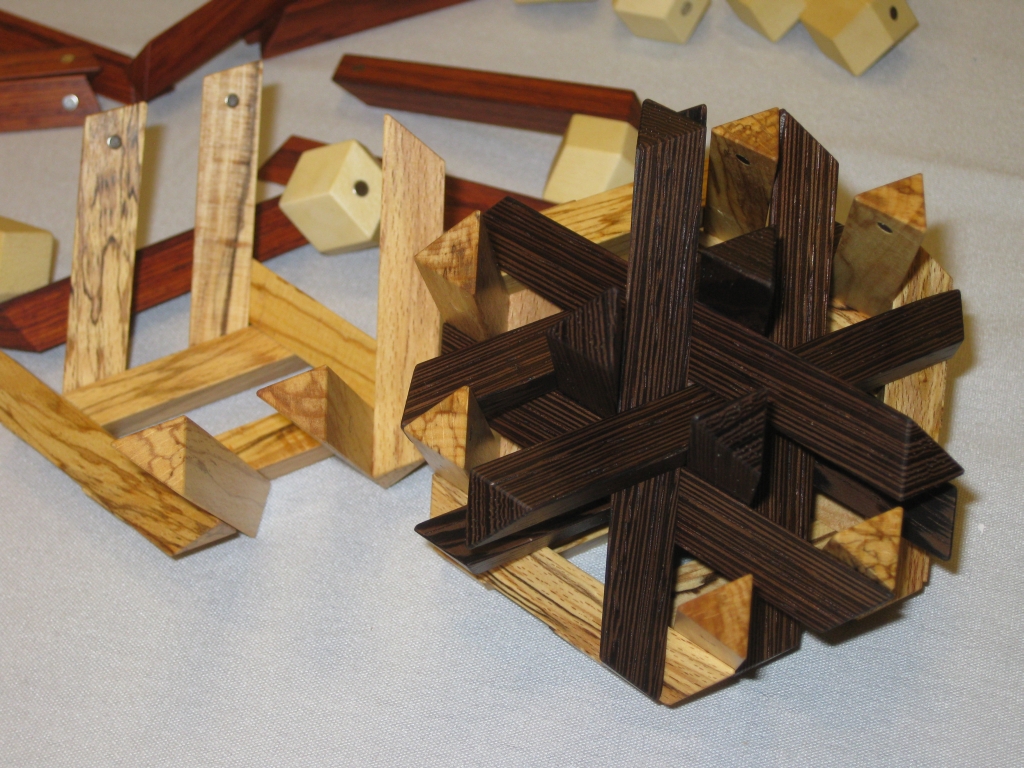

The Wenge ‘core’ disassembled leaving the inner cage. As you can see the magnets and the lattice hold the structure together without any support.

The Inner symmetric core. I love this structure.

Both parts of the inner core assembled separately. If you look closely, you can see the three sticks in each plane.

Here you can see how the inner code is nested inside the cage.

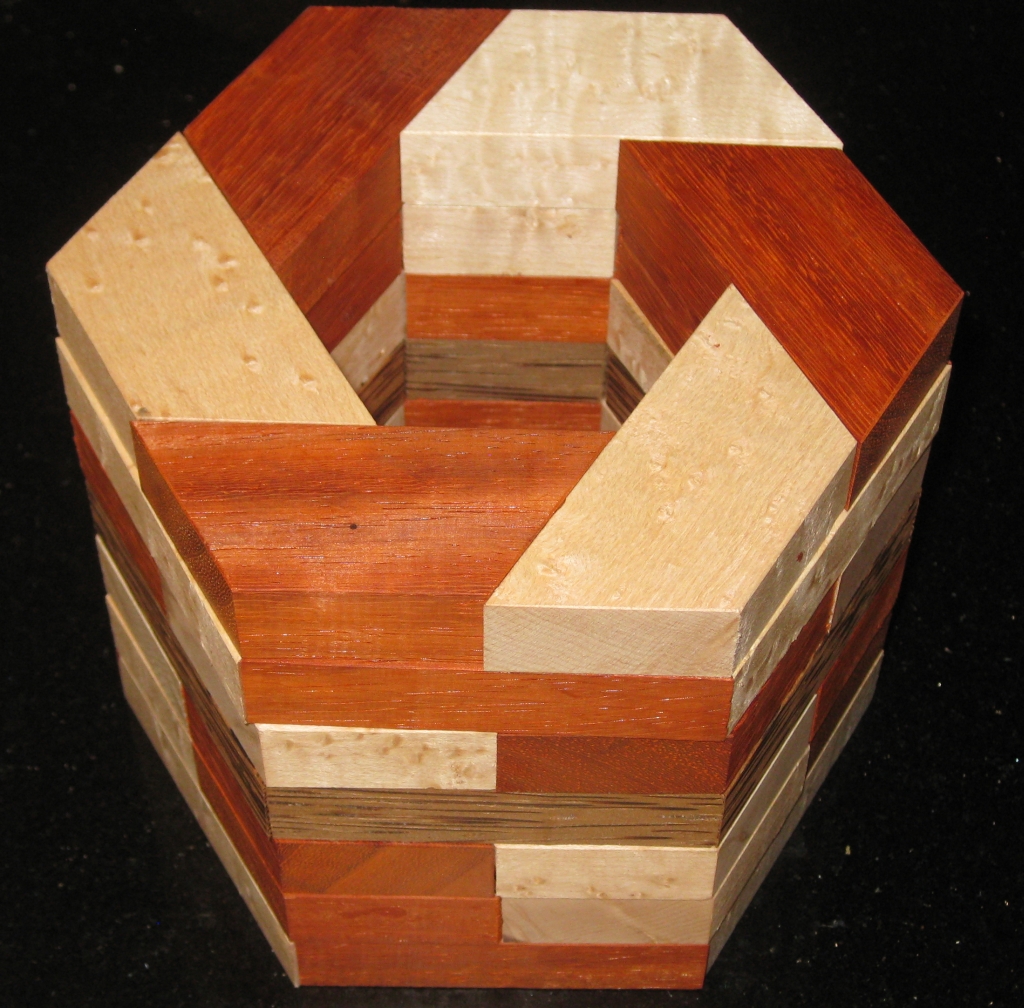

Chamfered Cube

Next up is the Chamfered Cube. This much smaller structure looks exactly as the name suggests, and really stands out with the pyramid shaped indents in each side of the cube. For some reason my photos of the remaining two puzzles didn’t turn out very well, so I’m having to use the competition photos from John Rausch’s site.

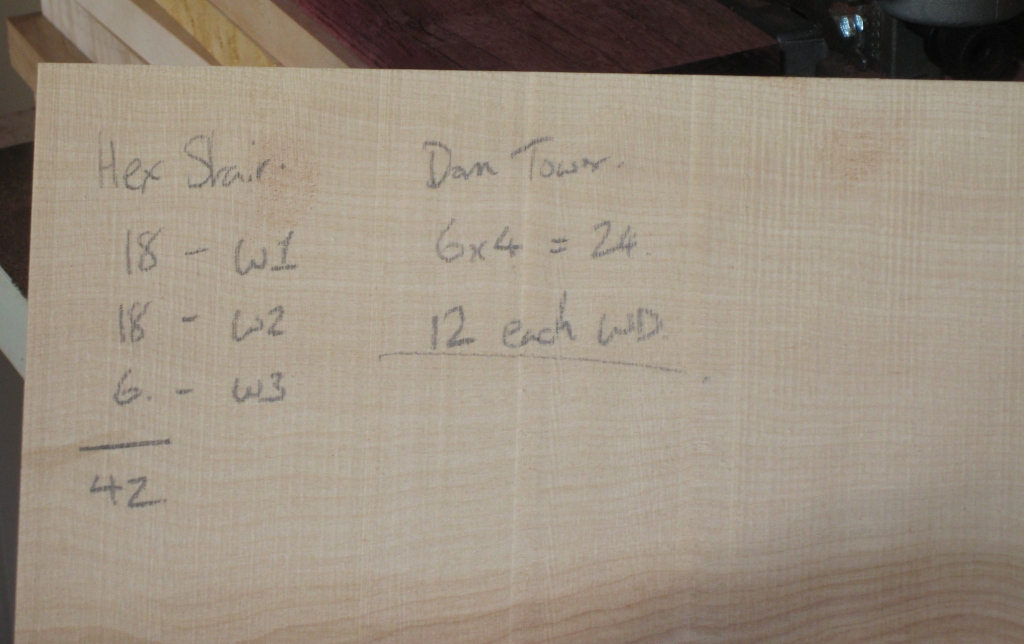

The goal for this puzzle is to use either set of 12 sticks to hold the 8 blocks in place at the corners of a cube and then to add the other set of sticks to make a large chamfered cube, which is the shape of the small white block that can fit in the center of the arrangement. This isn’t a difficult challenge as the shape of the ends of the sticks, and the blocks themselves guide you toward the correct solution. Made from Black Palm, Red Oak, and at a guess Chakte Viga it’s a striking looking puzzle.

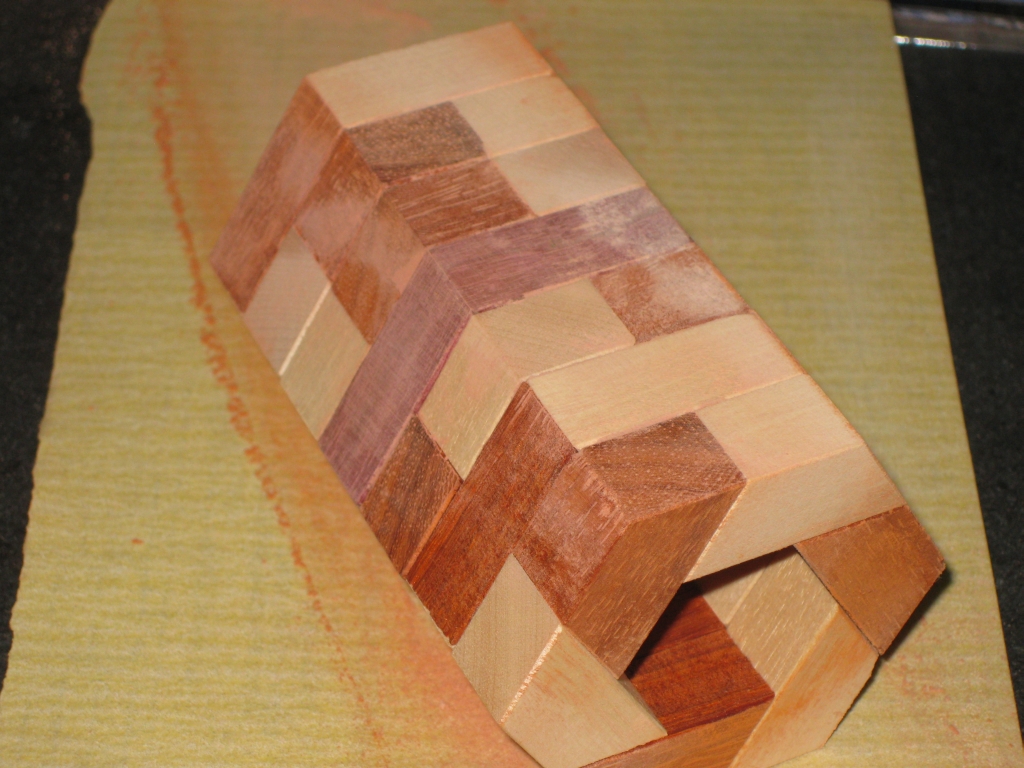

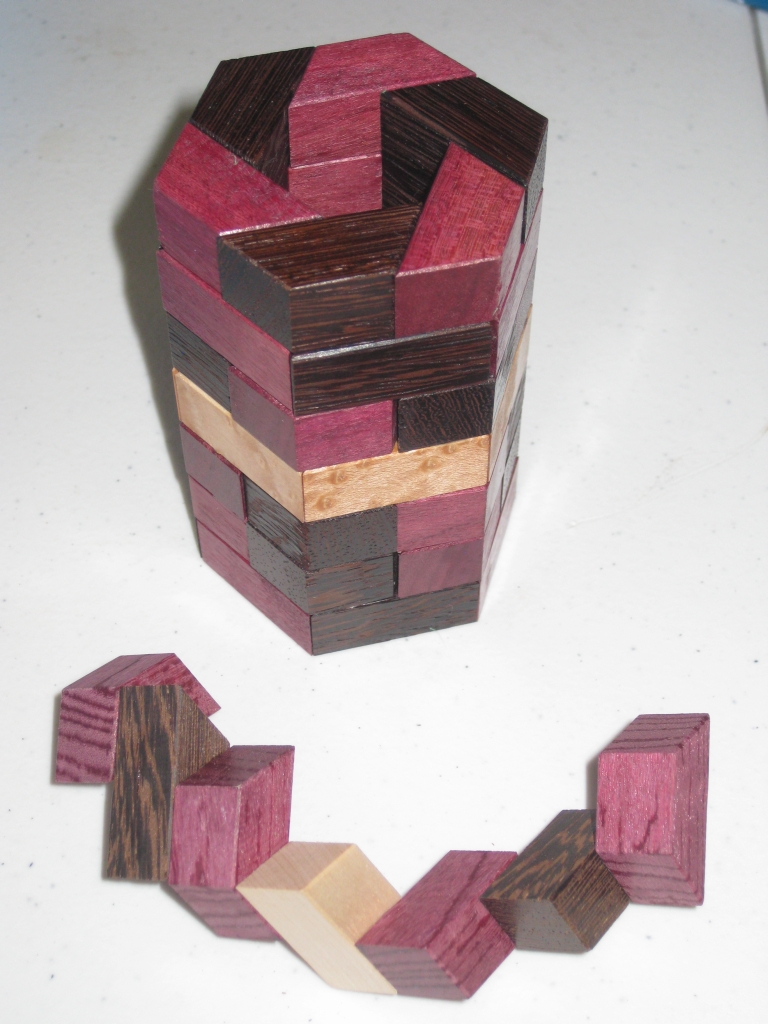

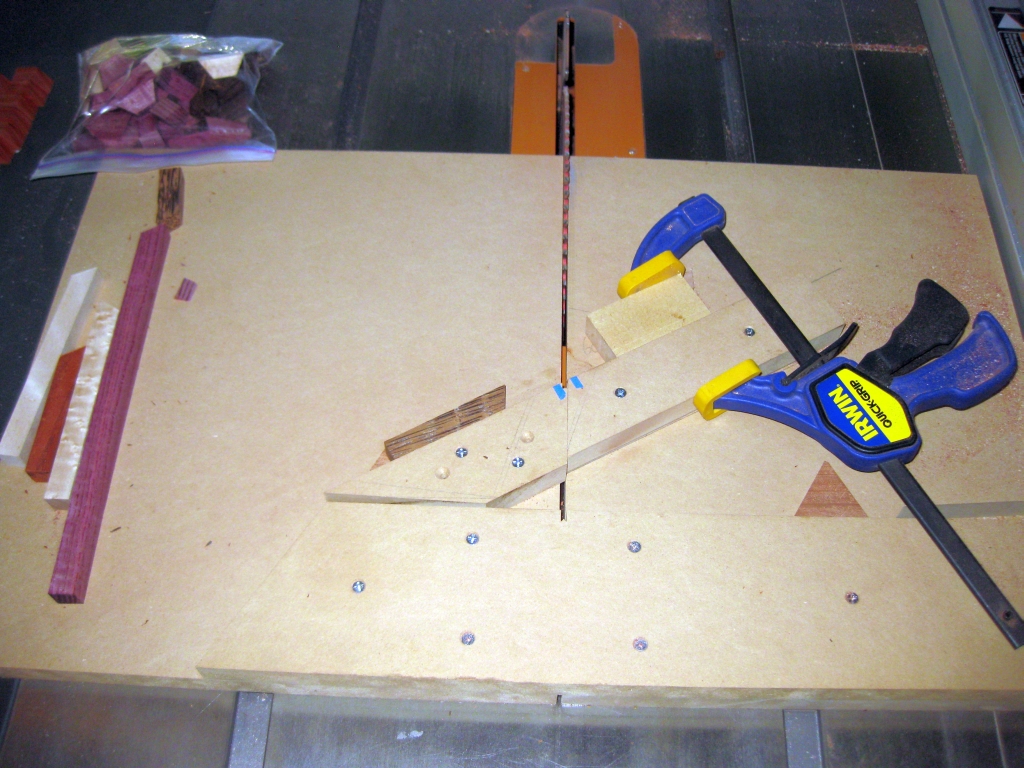

Double Duals

The third entry is Double Duals. Around the same size as the Chamfered Cube, this is another stunning looking puzzle. Made from Leopardwood, and possibly red oak (not sure on the lighter wood), this puzzle is almost an inverse construction of the previous puzzle. Rather than the sticks crossing through the centre of the structure, here they form the outer shell.

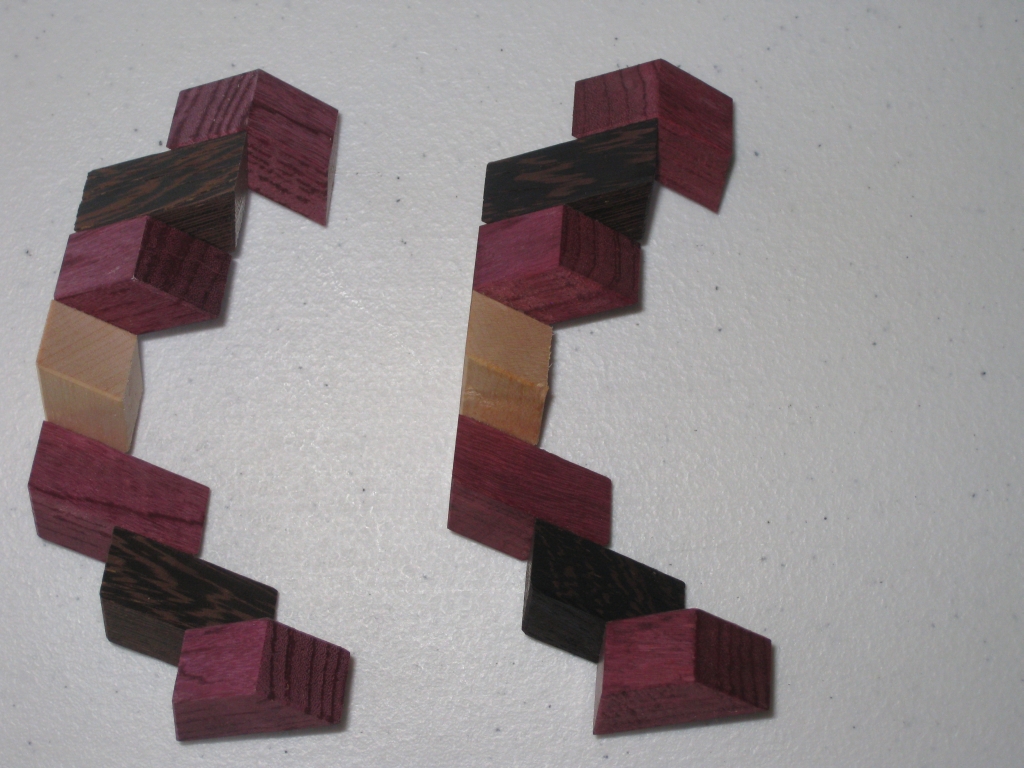

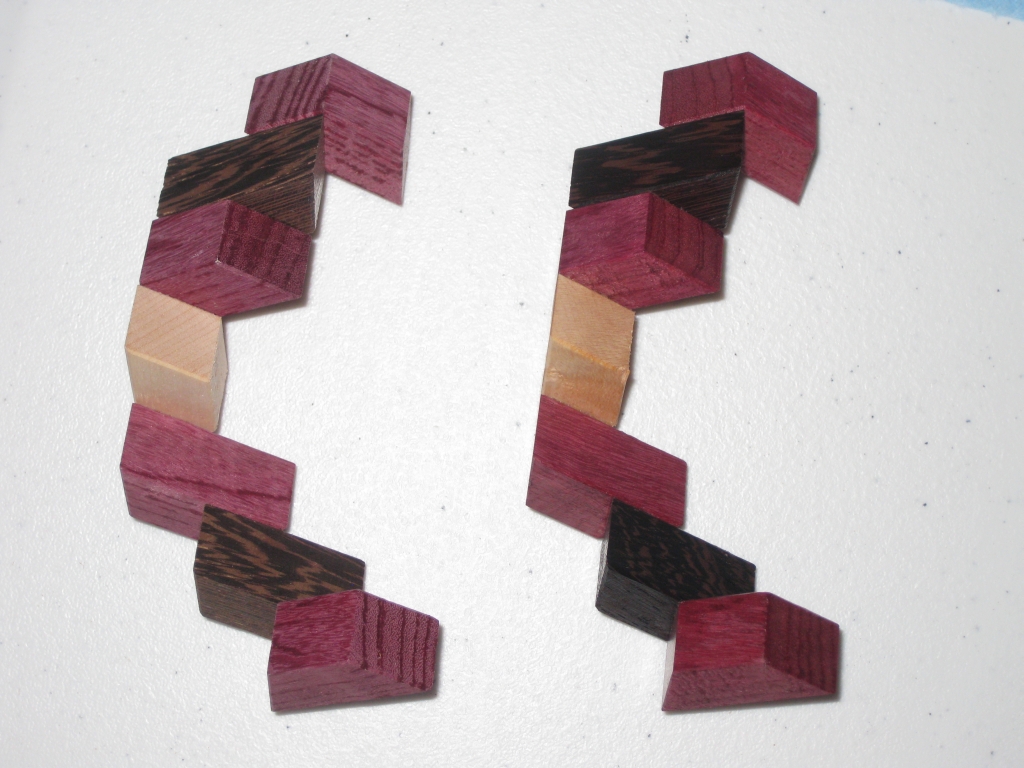

The goal of the puzzle is to make a pair of complementary arrangements such that each one contains blocks and 12 sticks symmetrically surrounding a center. Then put them together so that one is inside the other, and they both surround the block without magnets. Then repeat the entire process with each set of sticks making the opposite arrangement.

The clever part here is that as is hinted at, you can swap the sticks between the inner and outer construction. It’s a clever arrangement, and really needs to be played with to be appreciated.

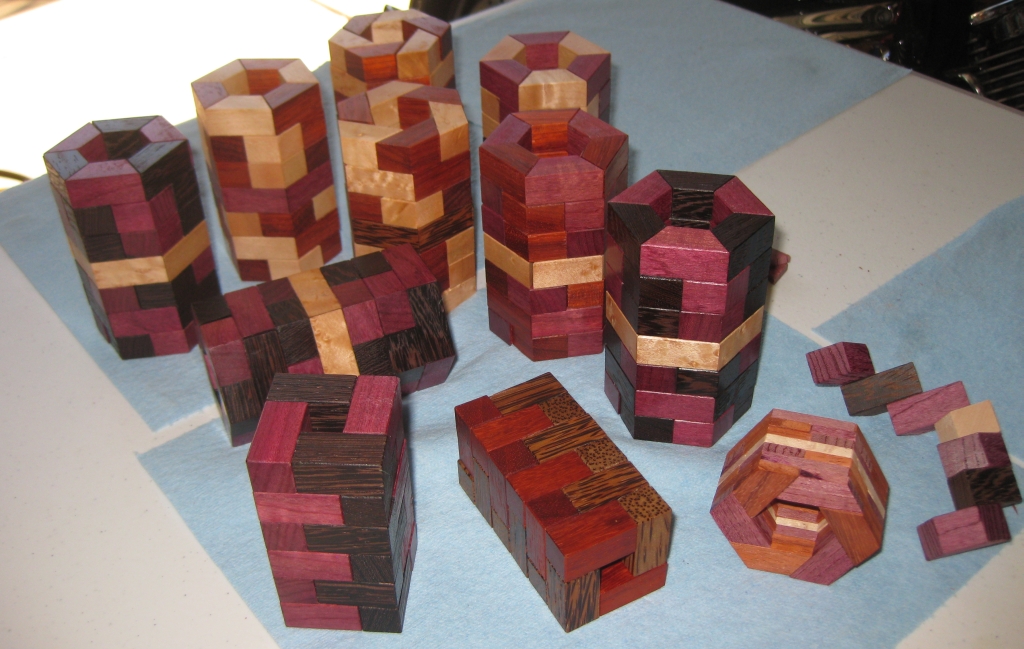

Other KoStick Puzzles from IPP

The competition entries weren’t the only appearance of Jane’s work over the weekend. It turns out that the IPP committee had arranged for Jane to make a very special little puzzle for each of the people who helped run and organise the events over the weekend. That came in the form of a tiny little Tetraxis puzzle.

Brian Pletcher was one of the people helping out and was given one of these beautiful little puzzles. as such I was lucky enough to be able to get a good look at it. It’s not a challenging assembly, however the way the blocks have been cut, there are multiple ways to assemble the pieces.

It’s a great looking puzzle, and something I’m sure the IPP organisers will be very happy to have in their collections.

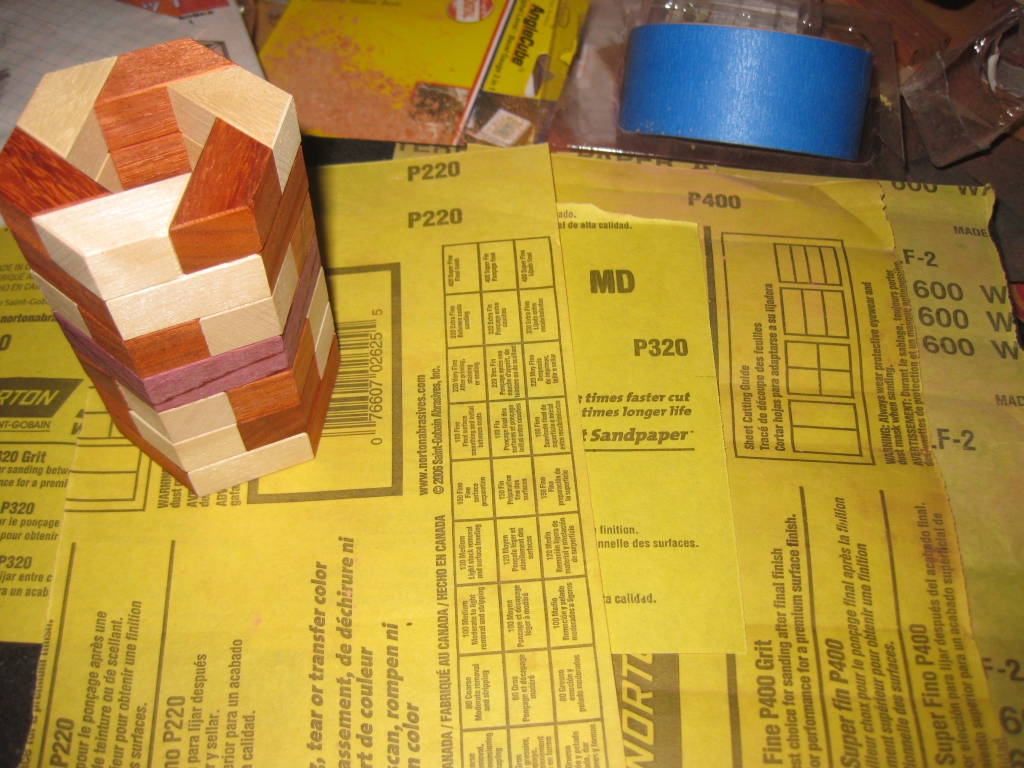

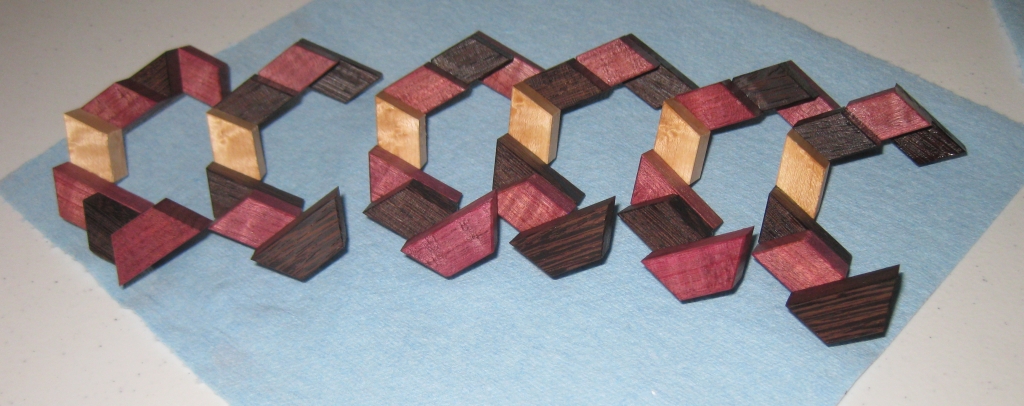

There was one final puzzle from the KoStick range which I played with over the weekend, which was thanks to John Rausch pulling a tube with some of Jane’s pieces out of his pocket and handing them to me. It turns out having talked with Jane that the puzzle was a 2 Layer Tetraxis array, knows as 4P1S. Now I have no idea what the code stands for, but for me it was probably the most challenging of the Tetraxis puzzles that I played with over the weekend.

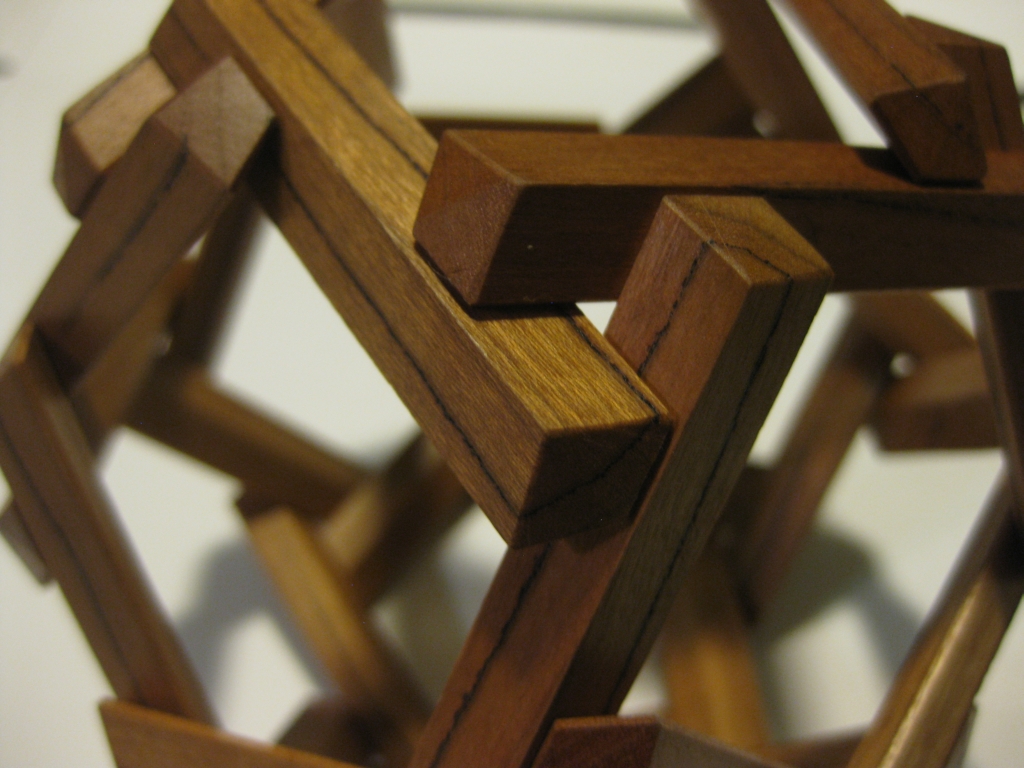

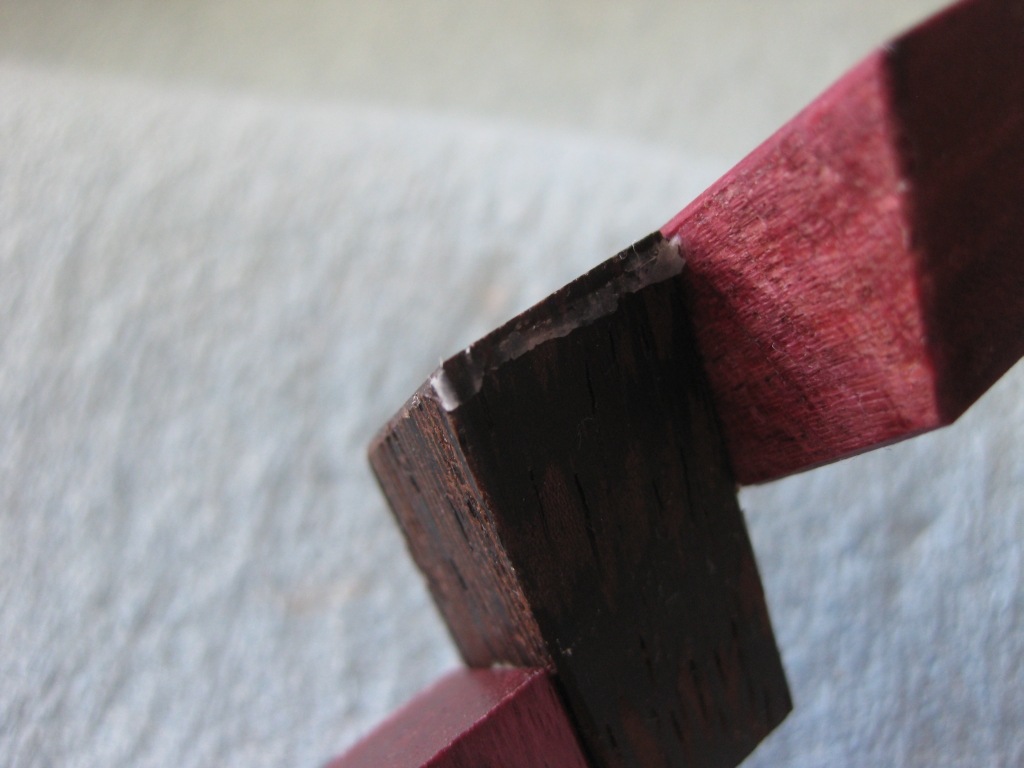

The version John had was in a single wood, however when I spoke to Jane about the puzzle she mentioned that she had two versions available. Seeing the puzzle above in Mahogany with Ebony and Holly tips I was quick to buy it from Jane. The puzzle is very similar to the Chamfered Cubes puzzle however there are no corner blocks to help with the assembly. As such this is a much harder puzzle to put together and as such I found it a lot of fun.

In total there are 24 sticks, 12 long and 12 short which need to be combined to make the shape above. It may look fairly simple, but it’s not as easy as it looks. Starting off, you make two sub-assemblies which you need to interlock, and then build up from there. Seeing how the first two interlock is the real challenge, and once they are in place, the rest comes together fairly quickly from there.

If I were to recommend one of the puzzles to get, it would be this last puzzle. I did!

Overall, Jane’s work is incredible, and really the photos don’t do it justice. It needs to be seen to be appreciated, and the movement of the pieces only really becomes magical when you have it in your hands. The wooden versions are well priced for the work that goes into them, but if you want a cheap version to be able to play with and get a feel for how the pieces interact before spending a lot of money, then I’d recommend some of the plastic versions which you can buy on their web shop.